Indian summers are getting hotter, but have we lost the ability to adapt?

Relevance: General Studies III: Geography, Environment, and Disaster Management

Why in the News?

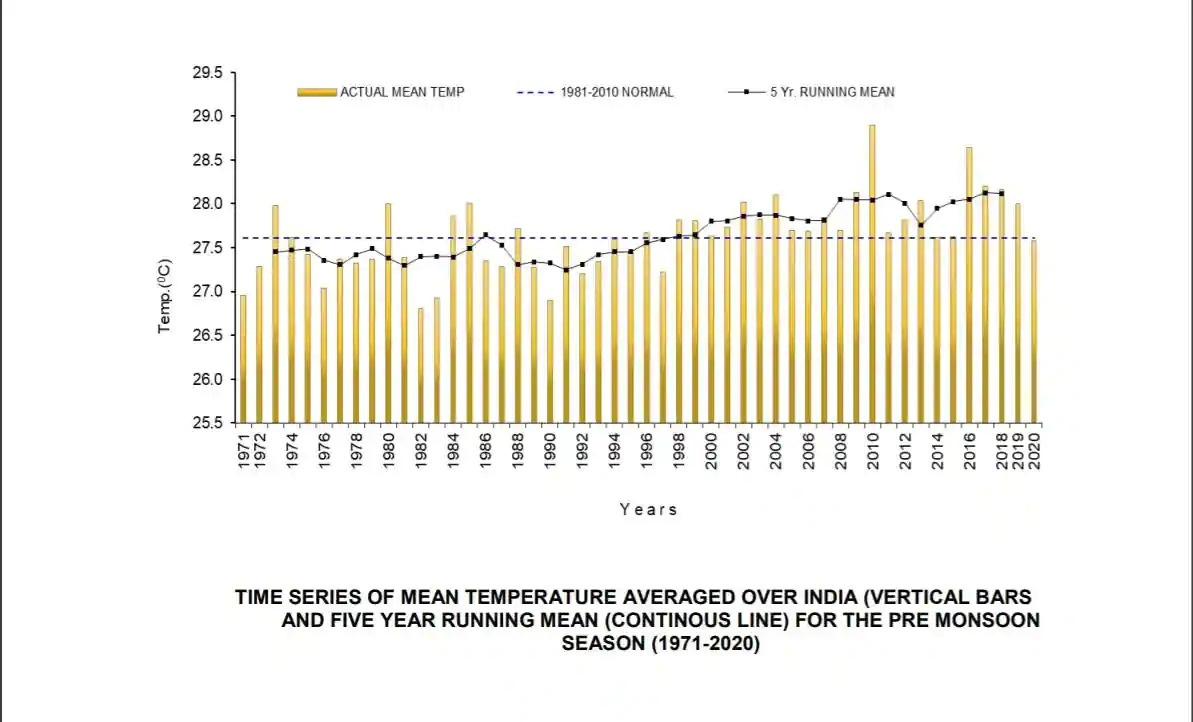

- India is witnessing an unprecedented rise in heatwave days. Between 2010 and 2024, these days increased by more than 200%, straining lives and livelihoods.

- The Global Burden of Disease study estimated over 155,000 heat-related deaths in India in 2021, many unrecorded in official counts.

- The 2022 heatwave severely impacted agriculture (e.g., wheat yields down by ~4.5%), triggered a power crisis, and exposed structural gaps in India’s climate adaptation.

- Reports by ANI, Princeton University’s Urban Nexus Lab, and researchers like Ajay Singh Nagpure highlight both the scientific urgency and socio-economic toll of heatwaves, sparking nationwide debate on heat resilience.

Background: India’s Relationship with Heat

Historically, Indians adapted to hot climates through:

- Architecture: Use of mud, lime, thatch, and stone to design homes that remained cool without electricity.

- Urban Design: Stepwells (baolis), water-cooled courtyards, perforated screens (jaalis), and shaded alleys formed passive cooling systems.

- Daily Routines: Rural life followed the sun – working early morning and late evening, resting during peak heat.

- Cultural Practices: Observances like Navtapa (May 25 – June 2), aligning with solar patterns, encouraged dietary changes and water conservation.

These weren’t merely cultural relics – they were scientifically sound and sustainable practices adapted to regional climates.

The Post-Liberalisation Shift

Post-1991 development favoured:

- Concrete and glass: Poor insulators, increasing indoor temperatures.

- Urban sprawl: Reduced green cover and water bodies.

- Rigid employment structures: Especially in informal sectors, where workers cannot adjust hours to avoid the heat.

- Policy and market gaps: Lack of incentives for climate-resilient materials or architectural design.

Thus, India’s organic ability to “live with heat” weakened as lifestyles, work patterns, and urban structures became incompatible with climatic realities.

Challenges

Escalating Human Toll

Underreported Heat Deaths

- Official records (2000–2020) show ~20,615 heatstroke deaths.

- Excess mortality studies estimate tens of thousands more. Most deaths occur:

- At home or in informal settings

- Without medical attention or certified documentation

Many are classified under generic causes (e.g., cardiac arrest, respiratory failure), masking the true burden.

Vulnerable Populations

- Outdoor workers (agriculture, construction)

- The elderly and children

- Migrant labourers

- Poor urban and rural households without cooling access

Economic Impact

- Labour productivity loss: McKinsey Global Institute warns India could lose up to 4.5% of GDP by 2030 due to heat-related productivity declines.

- Agriculture: 2022 wheat yield losses (4.5% nationally, up to 15% in some areas) due to heat stress.

- Energy grid pressure: Peak demand hit 207 GW during the 2022 wave, triggering blackouts and fuel shortages.

Healthcare burden: Rising cases of dehydration, kidney failure, and heatstroke, overwhelming hospitals.

Inadequate Policy Response

Urban Heat Action Plans (HAPs)

- Ahmedabad’s model (2014) – credited with reducing 1,190 deaths annually – has inspired others.

- However, most HAPs:

- They are advisory, not enforceable

- Lack of budget allocations

- Do not integrate with master planning

- Missed localised needs of the poor

- Rural Gaps

- No counterpart to urban HAPs

- Heat is not addressed in core schemes like:

- MGNREGA (no flexible work hours or shade)

- Gram Panchayat Development Plans (missing heat maps or budget)

- National Health Mission (no targeted heat risk management)

Way Forward: A Framework for Resilience

- Strengthen Heat Governance

- National Policy Mandate:

Make HAPs mandatory under the Disaster Management Act, 2005

Integrate heat resilience into the Smart Cities Mission, PMAY, and AMRUT.

Assign Climate Officers in cities and districts to:

Conduct local vulnerability mapping - Coordinate inter-departmental heat response

Institutional Roles Defined:

- IMD: Predictive heat alerts

- NDMA & SDMAs: Policy and coordination

- ULBs & Panchayats: Ground implementation

Rural Heat Action Plans

- Develop customised rural HAPs leveraging:

MGNREGA for shaded workspaces and staggered shifts - Jal Shakti Abhiyan to revive traditional water sources

- Community outreach via ASHAs, AWWs, Panchayat volunteers

Promote restoration of:

- Stepwells, ponds, and tree groves

- Traditional housing norms with breathable materials

- Heat-Resilient Infrastructure

- Urban Areas

Mandate:

- Reflective rooftops and passive cooling designs

- High albedo surfaces and green roofs

- Rainwater harvesting is linked to urban microclimate management

Real-estate policy:

- Incentivise climate-sensitive materials

- Penalise excessive use of heat-absorbing concrete/glass

Building Code Reform:

- Integrate passive cooling norms in the National Building Code

- Support pilot retrofitting projects in hotspots

Rural Areas

- Promote vernacular architecture via PMAY-Rural

- Disburse District Mineral Funds to support:

- Water tanks

- Shade structures

- Tree plantation

- Improve Risk Communication

Multilingual, multimodal advisories:

- Local radio, loudspeakers, wall posters, street plays

- Clear interpretation of “feels like” heat

Use trusted messengers:

- ASHA workers, school teachers, Gram Sevaks

- Develop public infrastructure:

- Cooling shelters in public parks, bus stops, and schools

- Education and Behavioural Nudges

- Integrate heat safety in school curricula

Promote:

- Traditional drinks like sattu and buttermilk

- Community kitchens during peak heat

- Launch summer heat awareness weeks in schools and Panchayats

- Financing Resilience

Leverage:

- 15th Finance Commission’s Climate Grants

- District Mineral Foundation Funds

CSR budgets from local industries - Create a dedicated Heat Adaptation Fund under the NDMA for local innovations

Conclusion

India is not merely facing warmer summers; it is confronting an era of climate extremes, where adapting to heat is no longer optional. Ironically, the knowledge needed to cope with it – passive cooling designs, climate-resilient routines, water conservation systems – already exists within the country’s rich heritage. The challenge lies not in discovery but in deployment. True resilience will not emerge from emergency advisories or isolated initiatives but from systemic change: in governance, infrastructure, communication, and community engagement. India must rediscover and reinforce its adaptive muscle – blending traditional wisdom with modern science – to confront the heatwaves of the future with strength, clarity, and compassion.

MAINS PRACTICE QUESTION

Question: “India is not merely facing warmer summers; it is confronting an era of climate extremes.” In light of this statement, critically examine why India’s traditional heat adaptation mechanisms have declined and assess the systemic governance, policy, and socio-economic reforms required to build heat resilience. (250 words)

PRELIMS PRACTICE QUESTION

Questions: About India’s heatwave adaptation strategies, consider the following statements:

- Traditional Indian architecture employed passive cooling techniques such as perforated screens, stepwells, and water-cooled courtyards to regulate indoor temperatures.

- The Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan (HAP), although credited with saving lives, is legally binding and has been uniformly implemented across all Indian cities.

- Rural areas are currently covered under national-level Heat Action Plans, which are integrated with schemes like MGNREGA and Jal Shakti Abhiyan.

- The National Disaster Management Act, 2005, mandates state governments to formulate and enforce climate-specific Heat Action Plans.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

A. 1 only

B. 1 and 4 only

C. 2 and 3 only

D. 1, 2 and 4 only

Correct Answer: A. 1 only

Explanation:

- Statement 1 is correct: Traditional techniques such as jaalis, baolis, and shaded courtyards were passive cooling systems.

- Statement 2 is incorrect: The Ahmedabad HAP is advisory, not legally binding.

- Statement 3 is incorrect: Rural areas lack formal HAPs and integration with core schemes.

- Statement 4 is incorrect: The DM Act does not yet mandate HAPs; it is suggested as a reform.