Why India Must Get the Caste Census Right

INTRODUCTION

The Government’s recent decision to include caste enumeration in the upcoming Census marks a transformative moment in Indian policymaking. Far from being a concession to identity politics, caste enumeration is an act of acknowledgement, a mirror reflecting the socio-economic realities of India. It is a foundational step towards evidence-based policymaking in pursuit of a more equitable and inclusive society.

Historical background

- Post-Independence India adopted a dual strategy: abolishing caste-based discrimination while pursuing social justice through reservations. This contradiction, often described as policy schizophrenia, stemmed from a refusal to officially acknowledge caste.

- The exclusion of caste enumeration, except for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), reinforced a flawed ideal of caste-blind governance, which neglected the lived realities of millions. While the Constitution mandates social justice through affirmative action, including reservations in education, employment, and politics, implementing these policies effectively requires precise, disaggregated caste data.

- The Supreme Court has consistently affirmed that caste is a legitimate proxy for identifying social and educational backwardness.

Learning from Past Failure

- The failed Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011 is a cautionary tale. Conducted without legal authority and technical expertise, the SECC produced an unusable dataset listing 46 lakh castes due to methodological flaws. Open-ended questions, untrained enumerators, and the absence of standardised caste classifications led to chaos.

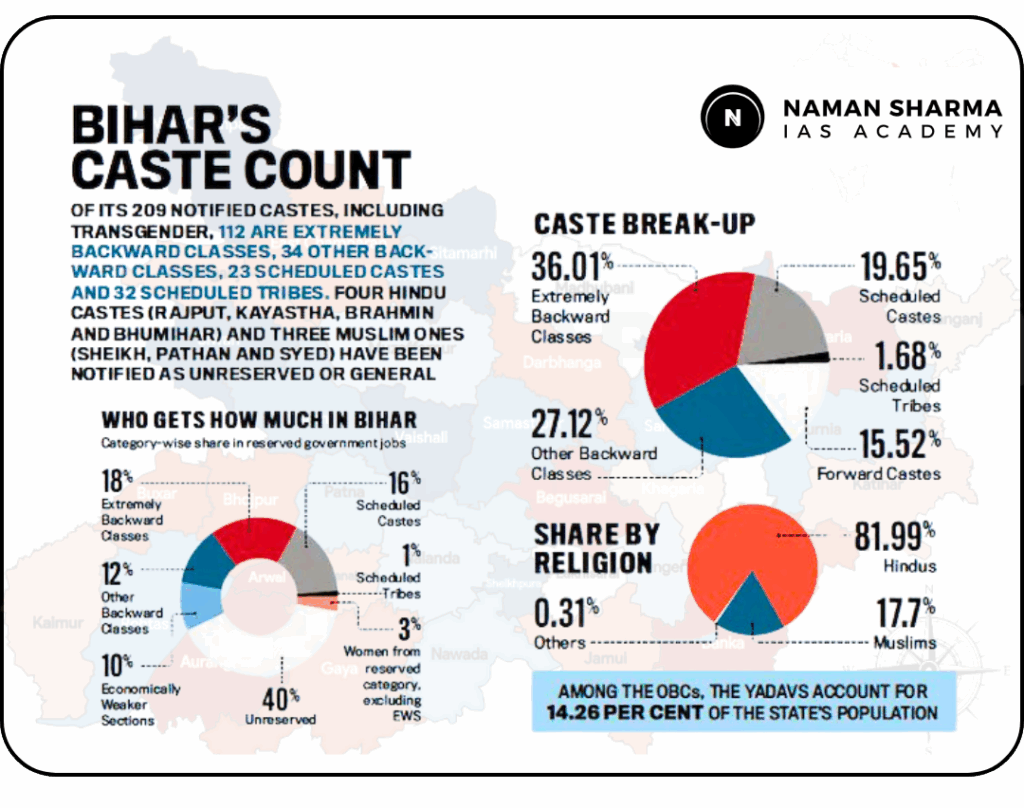

- In contrast, Bihar’s 2022 caste survey offers a successful model. By using a vetted list of 214 State-specific castes and structured enumeration methods, the survey achieved clarity and credibility. This proves that a well-planned and legally backed caste census is feasible.

The Case for Caste Data:

- Caste enumeration is not merely a political gesture; it is a legal and administrative necessity. The 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, which mandated OBC reservations in local governance, require granular, area-specific caste data.

- Furthermore, the inclusion of Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) among upper castes in reservation policies in 2019 further underlines the need for comprehensive data covering all caste groups. The current reservation system operates in an evidence vacuum, making it susceptible to manipulation by dominant groups.

- Limited existing data shows stark disparities: a small number of OBC castes dominate reservation benefits, while many receive little or nothing.

For example,just 10 OBC castes receive 25% of all reserved benefits, while 38% of OBC castes receive only 3%, and 37% are entirely excluded.

- Such inequities underscore the need for accurate data to prevent elite capture, enable rational sub categorisation, and refine the definition of the “creamy layer.”

Rohini Commission

- It was constituted in 2017 under Article 340 of the Constitution with the approval of the President of India.

- Article 340 empowers the President of India to appoint a commission to investigate issues concerning OBCs and make recommendations to improve their situation.

- Before constituting the Rohini Commission, the Centre had granted the National Commission for Backwards Classes (NCBC) constitutional status by the 102nd Amendment Act, 2018.

Highlights on Caste Census Decision

Digital Mode & Drop-Down Caste Directory

- For the first time, the Census will be conducted in digital mode, using a mobile app.

- A new “Other” column with a drop-down caste code directory will be included beside the SC/ST column. The software is currently being tested to ensure smooth implementation.

About 30 lakh government officials will need retraining for the new digital format.

The Census will occur in two phases:

- Phase 1: House listing & housing schedule (31 questions; already notified in 2020).

- Phase 2: Population enumeration (28 questions; tested in 2019, yet to be officially notified).

Directory Development & Testing

Major Policy Shift After Decades: The CCPA’s approval to include caste data in the upcoming census marks the first comprehensive caste enumeration since 1931 (excluding SC/ST data).

Inconsistent State-Level OBC Lists

- Different states have varying OBC lists and sub-categories like Most Backwards Classes, complicating efforts to create a standardised national caste database.

Significance for Delimitation & Women’s Reservation

- Implement a 33% women’s reservation in Parliament and State Assemblies.

- The new Census findings will be used to:

- Redraw Lok Sabha constituencies (delimitation).

Jharkhand Completes OBC Data Collection for Urban Local Body Quotas under Supreme Court’s “Triple Test”

- Recently, Jharkhand has completed its data collection on Other Backwards Classes (OBCs). This initiative aims to establish quotas for OBCs in urban local bodies.

About Triple Test

The triple test consists of three steps.

- First, a dedicated commission must empirically investigate backwardness in local bodies.

- Second, the commission specifies the required reservation proportion. This ensures that reservations do not exceed legal limits.

- Third, the total reservation for Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and OBCs combined must not surpass 50% of total seats.

The “triple test” is a legal framework laid down by the Supreme Court in Vikas Kishanrao Gawali vs State of Maharashtra (2021) to ensure that OBC reservations in local bodies are fair, evidence-based, and within constitutional limits.

Jharkhand’s Commission and Data Collection

- The Jharkhand OBC Commission was constituted in June 2023. Commission members studied Madhya Pradesh’s implementation of the triple test as a model.

- Data collection timeline: Data collection completed (between December 2023 – March 2024) and submitted (recently, several districts missed their submission deadlines) to the Commission.

Verification and analysis:

- For socio-economic and educational analysis, data will be handed to empanelled institutions like IIM, Xavier School of Management (XLRI) and Xavier Institute of Social Service (XISS).

- A final report will be submitted to the state government post-verification. Based on this, Jharkhand will determine OBC quotas in the 48 ULBs across the state.

OBC Classification in Jharkhand

- In Jharkhand, OBCs are divided into two categories.

- BC-I (Backwards Class I): More socially and educationally backwards; includes 127 castes.

- BC-II (Backwards Class II): Relatively better-off; includes around 45 castes.

- The Kudmi community, a subgroup of the Mahato/Mahto caste, is the largest OBC group, representing about 15% of the electorate.

Survey Focus and Methodology

- The survey aimed to identify OBC voters and estimate their share in urban local bodies. It differed from the nationwide caste census, focusing solely on urban areas.

- The survey gathered data on the political representation of OBCs across various government tiers.

- It included mayors, panchayat committee members, and the caste affiliations of Jharkhand’s MPS and MLAs.

Credible Caste Census

- Legal Framework: Amend the Census Act, 1948, to explicitly authorise caste enumeration and protect it from political interference.

- Institutional Expertise: Assign responsibility to the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, not to non-specialist ministries.

- Standardised Questionnaire: Employ closed-ended, drop-down-based forms with coded caste identifiers to avoid ambiguity.

- State-Specific Lists: Collaborate with State governments, sociologists, and communities to prepare caste lists, followed by public feedback.

- Enumerator Training: Ensure region-specific training with practical guidance on caste identification.

- Digital Tools: Use handheld devices preloaded with validated options to minimise manual errors.

Conclusion

- India has enumerated nearly 2,000 SC and ST castes since 1951 with consistency and accuracy.

- Extending this enumeration to the remaining OBC and upper-caste groups, estimated to be around 4,000 and mostly State-specific, is not only manageable but also essential.

- The delayed 2021 Census offers a unique opportunity to close this long-standing data gap and without caste data, the promise of social justice remains unfulfilled and policy continues to drift in darkness.

- The moment for delay has passed. The time for a credible, comprehensive caste census is now.

MAINS PRACTICE QUESTION

Question: A credible caste census is essential not just for ensuring social justice but also for improving the effectiveness of governance. In light of this statement, critically examine the significance and challenges of conducting a comprehensive caste enumeration in India.

PRELIMS PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. Regarding the inclusion of caste enumeration in the upcoming Census of India, consider the following statements:

- The Census Act, 1948, currently provides a specific legal mandate for caste enumeration beyond Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

- The failure of the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011 was primarily due to the absence of legal backing, standardised caste codes, and technical expertise.

- The triple test laid down by the Supreme Court requires empirical data collection, justification of quota proportions, and a cap on the total reservation across SCs, STs, and OBCs at 60% of the seats in local bodies.

- Bihar’s 2022 caste survey achieved higher data reliability by using a pre-vetted list of state-specific castes and structured digital enumeration methods.

Which of the above statements are correct?

A. 1 and 3 only

B. 2 and 4 only

C. 1, 2 and 4 only

D. 2, 3 and 4 only

Answer: B. 2 and 4 only

Explanation:

- Statement 1 Incorrect

- The Census Act, 1948, does not currently provide a specific legal mandate for conducting caste enumeration beyond SCs and STs. Amendments are being proposed to allow explicit legal backing for such enumeration.

- Statement 2 Correct:

- The Socio-Economic and Caste Census SECC 2011 failed due to methodological issues, including the lack of legal authority, open-ended questions, the absence of standardised caste lists, and untrained enumerators.

- Statement 3 Incorrect:

- The Supreme Court’s “triple test” (Vikas Kishanrao Gawali vs. State of Maharashtra, 2021) caps total reservation at 50%, not 60%, across SCs, STs, and OBCs in local bodies.

- Statement 4 Correct:

- Bihar’s 2022 caste survey is considered successful. This is because it utilized a vetted list of 214 state-specific castes and a structured, well-planned method. Consequently, it demonstrated the feasibility of collecting accurate caste-based data when properly executed.