Scheme-Based Workers in India: Challenges, Identity & Policy Gaps – UPSC GS2/GS2 Analysis

Relevance to GS2: Social Justice and Welfare Policies

Case Study Material for UPSC Essay/GS2

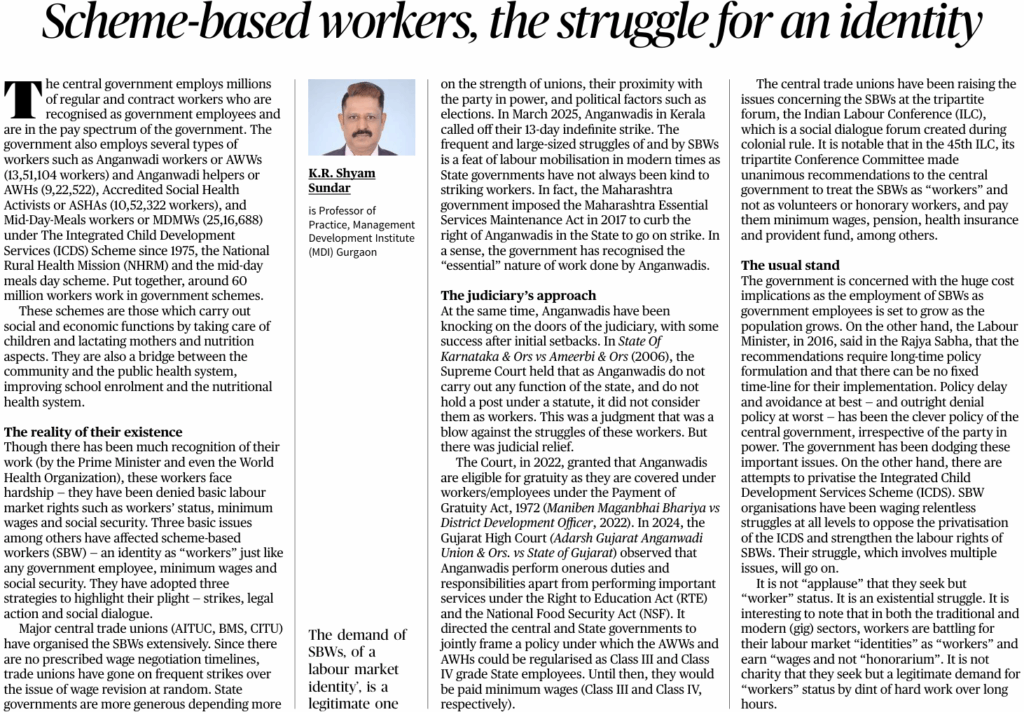

In the enormous expansion of India’s welfare architecture, the front-line worker depends on services on a large scale, but often on invisible, plan-based workers (SBW). Planned under major social welfare programs such as Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), National Health Mission (NHM) and the Mid-Day Meal (MDM) scheme, these workers work as bridges between the state and society, which facilitates the distribution of health, nutrition and educational services. Nevertheless, despite its basic role, SBW is denied regular recognition, fair wages and social security.

The Backbone of Welfare

- The government of India works with millions with different abilities. While ordinary and contractual employees are recognised under the workplace and are included in the formal wage structure, a significant part of the working group remains outside this safety net.

- Anganwadi workers and assistants, recognized social health workers (Ashas), and meal workers in the middle of the day, who are employed in all major schemes for the social sector, represent this invisible workforce.

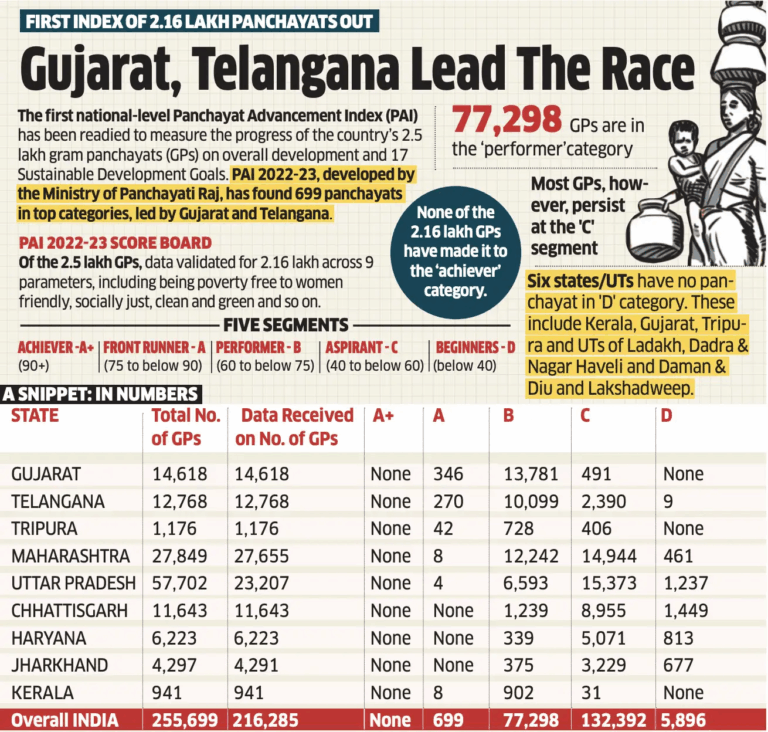

According to Government Data:

- Anganwadi Worker (AWWS): 13.51,104

- Anganwadi Assistant (AWHS): 9,22.522

- Recognised social health worker (Ashas): 10.52,322

- Mid-Day Meal Workers (MDMWS): 25,16,688

- Together, this group forms a formidable section – about 60 million workers of India’s social welfare machines.

- AWWS and AWHS provide nutritional help to children and breastfeeding mothers, monitor hair growth and provide education before school.

- Ashas facilitates society’s participation in the public health system and plays an important role in mothers’ and children’s health services.

- MDMW -er prepares and distributes food to millions of schoolchildren daily, a plan that is credited to improve registration, storage and children’s nutritional status.

An Unequal Social Contract: Denial of Rights

- Despite their inevitable contributions, the scheme-based workers are not recognised by the government as formal employees.

- Their commitment is described in nature as “honoured” or “voluntary”. They receive a fee, not pay; There are no provisions for minimum wage, social security or services such as Provident Fund or Health Insurance.

- This structural exclusion keeps them in the periphery of labour rights and reinforces their invisibility in political frameworks.

Three mutual relationships dominate their struggle:

- Legal identity as “workers”: Compulsory minimum wage according to the workover

- Extensive social security benefits: This is not just financial requirements, but is an existing argument for recognition in the labour market in India – a recognition that legalizes their work, ensures their livelihoods and confirms their dignity.

The government’s reasoning and development

- The primary argument presented by the government is tax controversy. The recognition of SBW as state employees will increase the expenses, especially the extent of welfare schemes. However, this attitude reflects a narrow concept of tax judgment that prefers budget control over social justice.

- In some quarters, attempts are made to privatise welfare schemes – a step that threatens to reduce SBW rights and dilute responsibility in service distribution.

- Proposals to outsource the middle of the day meal regulations for Anganwadi services and private institutions have strong opposition from trade unions and civil society.

- By preparing SBWs as “volunteers” and their remuneration, the state’s employers absorb themselves from the responsibility. This semantic maneuver effectively provides these workers in formal work data and deprives them of access to legal rights.

Comparative Approach: Work recognition in informal and gaming economies

- The SBWS match reflects a large working phenomenon in the Indian identity crisis in informal and stage-based employment. Whether it is a gigantic worker of digital platforms or volunteers in society, these categories have emerged as a common strategy to ignore the working laws that refuse to recognise these categories as “workers”.

The way forward: politics and ethically weakening

- A transformative change is required to remove the requirements of SBW. This change should be multi -dimensional, including legislative improvement, administrative involvement and moral reurement.

- Legal recognition and codification: A statutory recognition of SBW in the form of “workers” is necessary. A separate legislative structure or change (for example, salary and social security code) in the existing workover should cover the scheme workers, guarantee minimum wages, drinking money, pension and health coverage.

- Structured wage policy: The current arbitrary system for the fee shall be in accordance with the minimum wage law, with a structured and time -time-revised payroll system. Regional inequalities in pay should also be taken up to ensure equal dignity in states.

- Social Security Provision: should be included under the Staff State Insurance (ESI) and Provident Fund (EPF) schemes for employees. Where direct integration is unforgivable, with sufficient budget distribution, tailor-made welfare schemes and portability of benefits should be introduced.

- Representation and dialogue: An institutional platform should be set up for regular communication between SBW, their unions and the government. The Tripartite model of ILC should be renewed and binding in its recommendations related to informal workers.

- Stop privatising welfare work: Public welfare should remain a state responsibility. Privatisation dilutes responsibility, increases uncertainty and weakens the state’s constitutional mandate as a supplier of socio-economic justice.

Conclusion: recognised as a right, not a reward

- The struggle for SBWs is not a fleeting resistance. It is a continuous movement for identity, dignity and justice. Their requirement for the status of the employee lies in the constitutional promise of equality and the instructions of state policies that aim to secure vibrant wages and human working conditions.

- As a welfare state, India cannot take the risk of closing an eye for systemic utilization of those who are ahead of its public service distribution. A democracy honoring the inhabitants should start by honoring its workers – especially those who take care of their children, fix the sick and feed their hungry.

PRELIMS PRACTICE QUESTION

Q: Which of the following best reflects the core issue faced by Scheme-Based Workers (SBWs) in India?

A. They receive irregular payments and often strike for better schedules.

B. They are recognised as state employees but lack skill development programs.

C. Despite delivering essential public services, SBWs are denied legal worker status and associated rights.

D. Their main demand is to privatise welfare services for efficiency.

Correct Answer: C

Explanation: The central issue is the lack of recognition as formal employees, leading to the denial of minimum wages, social security, and basic labour rights.

MAINS PRACTICE QUESTION

Question: “Order-based activists (SBW) are the spine of India’s welfare distribution, but are marginalised by labour rights.” Analyse this statement regarding their legal status, socio-economic challenges and neglect of politics. In addition, measures are proposed to ensure proper recognition and security.