Nutrition as Empowerment: The Ingredient to Turn Around Nutrition Outcomes

Nutrition as empowerment is a powerful approach to tackling India’s malnutrition crisis. By improving access, awareness, and sustainable practices, it strengthens public health and supports long-term development.”

Introduction: A Hunger Beyond Food

India’s huge free foodgrain program for 800 million people is one of the world’s largest food security initiatives. Still, even when we appreciate its scope and intentions, the endurance of hunger and malnutrition, especially among women and girls, is a serious contradiction. Despite a network of continuous economic development and welfare schemes, India’s nutrition maps reflect deep inequalities by gender.

There is an unpleasant truth at the heart of this challenge: malnutrition in India is not only a health problem, but a structural and gender injustice. This is the result of uneven power, tangled norms and systemic errors that push women during the nutrition pyramid.

Understanding the Crisis: The Gendered Face of Malnutrition

- The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) exhibits an annoying fact:

- Fifty-seven per cent of Indian women (ages 15-forty nine) are anaemic, compared to just 26% of men.

- Nearly 1 in 5 women is underweight. Anaemia in girls has expanded, now not decreased, from 50% to 57% between NFHS-4 and NFHS-5.

- Half of Indian women lack autonomy in spending their earnings, impacting dietary alternatives and health decisions. These data endorse that gender is not a marginal variable’s far central to India’s vitamins crisis.

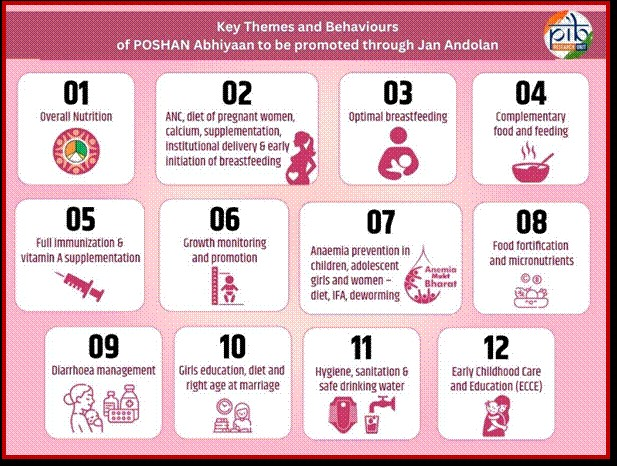

POSHAN Abhiyaan

- Launched in 2018, the Prime Minister’s Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nourishment (POSHAN Abhiyaan) changed into estimated as India’s flagship programme to fight malnutrition.

- Focused on pregnant girls, lactating moms, adolescent girls, and youngsters below six, the project aimed to make India “malnutrition-unfastened” using 2022. It has been seen that developed into POSHAN 2.0, combining in advance schemes like ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services) and imparting a budget of ₹24,000 crore in 2022–23.

Only 69% of the price range had been utilised by December 2022.

- Anaemia and undernutrition remain stubbornly excessive, mainly among women.

- Clearly, the issue isn’t always pretty much investment, but about execution, cultural norms, and structural inequalities.

Limited Reach, Good Intentions

- While the POSHAN framework has made people aware, several structural issues cap its potential: The anganwadis suffer from underfunding, understaffing, and a lack of community interaction.

- Nutrition activities tend to be passively received rather than being actively linked with livelihood or empowerment programs.

- Behaviour change communication (BCC) is insufficient if women lack the means to buy or access nutritious food.

Structural and Social Barriers

- In many Indian households, girls and ladies eat last and least. This isn’t simply symbolic, it’s far structural. Cultural Norms and Household Dynamics.

- In patriarchal families, girls’ wishes are deprioritised. Food distribution reflects electricity: elders and guys devour first; women and girls frequently get leftovers.

- Lack of Decision-Making Power; NFHS-5 data suggests 49 % of women lack manipulate over spending their earnings. Financial dependence reduces their capability to demand or get right of entry to nutritious food.

- Invisibility of Women’s Labour: Women regularly work in the unpaid or casual sectors. Their financial contribution is undervalued, reinforcing the belief that they may be less deserving of family support.

Empowerment as a nutrition policy

Globally and in India, research continuously indicates that women empowerment is directly correlated with better nutrition results – for themselves and their families.

Evidence-based insight:

- Work on Nobel Prize winner Esther Duflo proves that the income in women’s income is spent more on health and nutrition.

- A region’s study among low-income Indian families found that women-controlled finances were low. Thus, economic empowerment is not a priority – it is fundamental to nutrition results.

Labour, Income, and the Power to Choose

- Self-employed women earn fifty-three % much less than men in comparable roles. This suggests a form of “operating poverty” where girls can be hired but continue to be economically disempowered, with little impact on over family choices or nutrients.

Recommendations

- Alignment with Livelihood Programmes: Nutrition initiatives need to harmonise with skill development and job schemes such as the NRLM (National Rural Livelihoods Mission). Anganwadis can be “nutrition and empowerment centres” providing hot meals, medical check-ups, and financial awareness classes under one roof.

- Gender-Responsive Budgeting: Dedicate funds for women’s nutrition and empowerment in the union and state budgets. Ensure improved utilisation of funds through decentralised planning and community accountability measures.

- Reform Anganwadi Ecosystem: Enhance wages and training for Anganwadi workers. Make them capable of providing multi-sectoral services (nutrition, counselling, livelihoods) rather than food distribution only. Create convergence with ASHAs, SHGs, and women’s collectives.

- Empower through Technology: digital instruments such as POSHAN Tracker and Jan Dhan accounts to transfer nutrition benefits directly to women. Provide digital inclusion to rural women by making mobile phones accessible, building digital literacy, and providing grievance redress systems.

- Gender-Just Nutrition Framework: If India plans to reach SDG-2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG-5 (Gender Equality), nutrition policy has to go beyond calories and iron tablets. Understand that malnutrition is a result of disempowerment, not poverty. Recognise that food security among women involves agency, autonomy, and access.

Highlight

- POSHAN Abhiyaan India’s 2018 flagship nutrition mission: now merged as POSHAN 2.0. Emphasis on women, children, and adolescent girls.

- NFHS-5 Data 57% of women (15–49 yrs) are anaemic: 1 in 5 are underweight, 49% don’t have control over expenditures. Funding Issue ₹24,000 crore funds allocated in 2022-23, but used only 69%. Implementation gap persists.

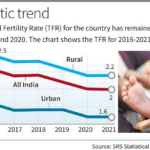

- FLFP: Increased to 33% (2021–22), but only 5% in formal salaried employment. Most earn much less than their male counterparts.

- Policy Convergence: Nutrition has to converge with employment schemes (NRLM), financial inclusion, and health services.

- Anganwadi Reform: Must be strengthened as convergence centres providing nutrition, training, and financial literacy.

- Recommendations: Empowerment-oriented monitoring targets, gender budgeting, digital technologies, and women-led self-help groups.

Conclusion

India will not solve malnutrition merely by handing out more food. The struggle has to target the invisible hunger of disempowerment. Women are not only victims of malnutrition, but also its solution. When the woman is empowered, well-nourished, and respected, not only does she do well herself, but she acts as a pillar to her children, community, and country. Nutrition, thus,needs to be reframed not as a food security issue, but as a gender justice imperative.

PRELIMS PRACTICE QUESTION

Q. Which of the following best captures the central argument of the article “Nutrition as Empowerment: The ingredient to turn around nutrition outcomes”?

A. Nutritional inequality in India stems primarily from poor infrastructure and underfunded welfare schemes that fail to provide enough food.

B. The persistence of malnutrition in India, especially among women, is largely due to poverty and lack of food availability in rural areas.

C. India’s battle against malnutrition requires a shift from calorie-based food distribution to a gender-empowerment-based approach, where nutrition policy is integrated with women’s economic and social agency.

D. Malnutrition can be eliminated through behavioural change, communication and targeted supplementation programmes under schemes like POSHAN Abhiyaan.

Correct Answer: C

Explanation:

- Option A: Incorrect: The article acknowledges underfunding and implementation issues but argues these are not the primary cause; it highlights structural and gendered inequalities.

- Option B: Incorrect: Poverty is a factor, but the article emphasises disempowerment, not scarcity of food alone.

- Option C: Correct: This captures the core thesis: that nutrition must be reframed as a gender justice issue, and empowerment (income, decision-making power, autonomy) is integral to improving nutritional outcomes.

- Option D: Incorrect: While behaviour change and POSHAN are mentioned, the article criticises their limited effectiveness without empowerment and structural reform.

MAINS PRACTICE QUESTION

Q.“Nutrition in India is not just a matter of food security, but a deeper issue of gender justice.” In the context of POSHAN Abhiyaan and NFHS-5 findings, critically examine the link between women’s empowerment and nutritional outcomes. Suggest policy measures to make India’s nutrition strategy more gender-responsive.(250 words ,15 Marks).