In India, Education Without Employment

Indian education unemployment is a growing concern as the gap between academic degrees and actual job opportunities widens across the country.

Despite many education reforms, our system fails to understand the changing job market, leaving graduates unprepared and unemployable. Despite the ambitious goals of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, India’s education system continues to suffer from low graduate employability, poor industry linkage, and a lack of innovative outputs. Critics argue that the system produces degrees with little market value and fails to meet the evolving demands of a knowledge-based economy.

- Accompanied by initiatives such as Atal Tinkering Labs, the introduction of coding in middle school, inclusive recruitment drives for Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe teachers, and the empowerment of Muslim girl students, the current administration asserts that it has broken free from the shackles of past governments.

- Educated unemployment refers to a situation where individuals with formal education, often higher education, cannot find suitable employment matching their qualifications. This paradox has deepened in India, as educational qualifications rise, employability and job prospects often decline.

- According to the ILO–IHD India Employment Report 2024, over 83% of India’s unemployed workforce are youth, and more than 65% of them have secondary or higher education. The graduate unemployment rate is around 29.1%, almost 9 times higher than that of illiterates.

Causes of Educated Unemployment

- Excess Supply of Graduates, Limited Job Demand:

- Universities rose from 642 (2011–12) to 993 (2018–19), with 3.74 crore students enrolled. However, graduate job creation has not kept pace, leading to market oversaturation.

- Poor Quality of Higher Education:

- NEP 2020 emphasises course flexibility, but neglects pedagogy and curriculum reforms. Many private colleges lack qualified faculty and infrastructure, leading to poor learning outcomes.

- Skill Mismatch Between Education and Industry Needs:

- Graduates lack skills in communication, problem-solving, digital literacy, and technical domains. A shocking 47% of graduates are unfit for industry roles despite formal education.

- Jobless growth:

- India lost 9 million jobs (2011–18); manufacturing shed 3.5 million.

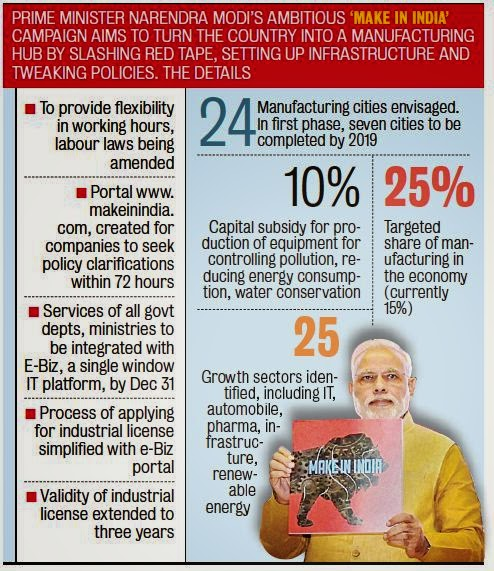

- “Make in India” failed to create jobs due to a capital-intensive focus. Lack of industry–academia collaboration (e.g., no industry members in NEP drafting panel) hinders curriculum relevance.

- Misleading Higher Education Rankings:

- Although 11 Indian universities entered the QS Top 500, India’s Category Normalised Citation Impact (CNCI) remains poorly ranked 16th out of 19 G-20 countries, reflecting low research quality despite increased quantity.

- Non-Transparent Megaprojects with Public Funds:

- Projects like IMPRINT, Akash tablet, and CSIR-NMITLI were launched with great publicity but lack publicly available data on outcomes, raising concerns about value-for-money and accountability.

- The employability rate in 2025 remains stagnant at 42.6%, a negligible shift from 44.3% in 2023.

- The education system, despite its expansive reach, disempowers rather than empowers, offering little value to students beyond paper credentials.The onus lies with the incumbent government to rectify systemic deficiencies.

- With NEP 2020 being the fourth attempt in a lineage of reformative documents following the Radhakrishnan (1948), Kothari (1966), and Officers’ Commission (1985), it is not a lack of policy but rather the absence of meaningful implementation and insight that cripples Indian education.

Reform

Lack of Implementation Mechanisms

- A truly effective education system should balance depth, which develops technical expertise and breadth, which enables adaptability in a fluid, AI-driven job market.

- NEP 2020, while conceptually flexible with its multiple entry and exit points, has only given rise to low-skill, poorly paid gig economy jobs. The NEP’s emphasis on superficial novelty, such as Indian Knowledge Systems and mother tongue instruction, remains unaccompanied by robust implementation mechanisms or industry input. Notably, the NEP drafting committee lacked representation from business or industry, a glaring oversight that undermines its claim to address employability and innovation.

National Education Policy (NEP) 2020

- Objective: Curriculum flexibility, vocational training integration, and skill-based learning.Challenges

- NEP’s multiple-entry–exit system has led to low-quality e-commerce jobs, not meaningful employment. Lacks proper implementation methodology and no industry participation in the drafting committee.

- Overfocus on course selection, neglecting course content relevance and quality.

Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY)

Objective: Provide skill certification and short-term training to youth. Challenges:Poor placement outcomes and weak monitoring mechanisms. Does not sufficiently bridge the industry skill gap.

Skill India Mission (2015)

Objective: Create a skilled workforce aligned with market demand. Coverage Gaps: India still has only 2.7% of the population vocationally trained, compared to 96% in South Korea. Mostly limited to entry-level, low-paying jobs.

Make in India:

Objective: Promote manufacturing and job creation in labour-intensive sectors. Issues: Manufacturing jobs declined by 3.5 million between 2011–12 and 2017–18. Focus remained on capital-intensive sectors, failing to absorb skilled labour.

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY) (2021)

Objective: Provide rural youth with market-linked skills and employment. Constraints: Limited awareness and weak rural infrastructure affect effective outreach and uptake.

National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) (2016)

Objective: Promote apprenticeships in industry and incentivise employers. Constraints: Low participation of firms and lack of integration with university curricula limit the impact.

Way Forward

- Align Curriculum with Industry Needs: Revise higher education curricula to reflect real-world skill requirements such as communication, critical thinking, digital literacy, and problem-solving. Over 47% of graduates are deemed unemployable due to such skill gaps.

- NEP reforms must shift from flexibility to content quality and pedagogy improvement. Expand Vocational and Digital Skill Training: Make vocational education integral to all degree programs and scale digital skills training. Focus on job-ready certifications tied to sector-specific demands.

- Promote Region-Specific Skilling and MSME Job Growth: Tailor skill development to local industry needs (e.g., textiles in Tamil Nadu, tourism in Himachal). Encourage MSMES and agro-industries that absorb local talent.

- Gender-Inclusive Employment Policies: Incentivise women’s employment with flexible work arrangements, childcare support, and safe workplaces. Female graduate unemployment is 34.5%, far higher than male unemployment (26.4%).

- Improve Data-Driven Monitoring of Outcomes: Establish a national tracking system for graduate outcomes, placement rates, and job tenure across institutions. Many schemes like PMKVY and DDU-GKY lack long-term tracking of job retention. Promote Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment: Provide credit, mentorship, and incubation for student entrepreneurs.

Conclusion

- India’s education-employment disconnect demands urgent reforms to align curriculum with industry needs, strengthen vocational training, and foster industry–academia collaboration.

- Without addressing skill mismatches and job creation, the demographic dividend risks becoming a demographic liability, threatening economic growth and social stability. India’s education crisis is not one of policy volume, but of execution, alignment with industry, and a focus on real-world outcomes.

PRELIMS PRACTICE QUESTION

Question 1: About the paradox of educated unemployment in India and the implementation of NEP 2020 and related skill development initiatives, consider the following statements:

- Despite high enrolment in higher education, the employability of Indian graduates has improved marginally due to a shift from rote learning to industry-driven curriculum reform.

- The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, though conceptually flexible, has resulted in a rise in low-skill gig economy jobs due to its weak implementation and lack of industry collaboration.

- The Skill India Mission has succeeded in bringing India’s vocational training coverage on par with developed nations such as South Korea, with a majority of the population now holding job-relevant certifications.

- The increasing number of Indian universities in global rankings masks underlying concerns about research quality and curriculum relevance, as reflected in India’s low CNCI among G-20 nations.

- Projects like IMPRINT and the Akash tablet, while ambitious in scope, lack outcome transparency and have raised questions about accountability in public fund utilisation.

Which of the above statements are correct?

A.1, 2, and 3 only

2, 4, and 5 only

C.1, 3, and 4 only

D.2, 3, and 5 only

E.1, 2, 4, and 5 only

Answer: B. 2, 4, and 5 only

Detailed Explanation:

- Statement 1 Incorrect:

- While enrolment is high, employability has not improved due to outdated curricula, poor pedagogy, and a lack of skill alignment. There’s no shift to truly industry-driven reforms yet.

- Statement 2 Correct:

- NEP 2020, though promoting flexibility (like multiple entry/exit), has not led to meaningful employment and is criticised for lacking industry input, leading instead to low-skill gig economy roles.

- Statement 3 Incorrect:

- India’s vocational training coverage is only 2.7%, compared to 96% in South Korea. The claim of parity is factually wrong.

- Statement 4 Correct:

- Though Indian universities entered the QS Top 500, the CNCI ranks 16th out of 19 G-20 nations, indicating poor research quality and content relevance.

- Statement 5 –Correct:

- Projects like IMPRINT and Akash tablet are criticised for a lack of publicly available outcome data, raising red flags on transparency and value-for-money.